Designing for Equity at Scale

Abstract

A U.S. based, national university access and persistence organization wanted to better meet the holistic needs of first generation, university-going students of color from low-income communities. They chose culturally relevant pedagogy as their framework to redesign the curriculum in an effort to meet the needs of their students and achieve better access and persistence outcomes. On the surface, a national, standardized curriculum is the opposite of culturally relevant. This produced an interesting case of a general design challenge: how do designers create a single curriculum that is culturally relevant and will be implemented across metropolitan regions that vary widely in local culture? What emerged was both an inclusive design process, and the creation of a series of tools and resources to support the implementation of a curriculum that was adaptable to local context while maintaining core content that all students needed. This paper will share the principles that provided the foundation for equity-centered collaboration and design experiences, a framework for designing a culturally relevant curriculum (or other educational materials) to be used across varying cultural contexts, and a process for implementing an equity-centered design process at scale. This toolkit can be utilized by curriculum designers, teachers, and organizational leaders to center equity and inclusion in their design processes and within their content and programming.

Introduction

Designing a standardized curriculum to be utilized across varying cultural contexts presents a challenge when local cultural values are inconsistent with the standardized curriculum (Bautista et al., 2021; Yang & Li, 2022). Equity-centered, standardized curriculum design is even more complex and appears oxymoronic on the surface: on the one hand, equity is both an outcome and a process in which resources are disproportionately redistributed to create systems and organizations that promote more equal opportunities and outcomes; and on the other hand, standardized curricula historically seek to impart a fixed set of inputs such as content, norms, and practices (Jurado de los Santos et al., 2020; Yang & Li, 2022). Meeting core curriculum content goals while making space for local context and culture is important for achieving equitable outcomes. We define equity and inclusion as relationships of power; to achieve equitable outcomes amongst people with marginalized and privileged social identities, power must be redistributed. We explore this general design challenge via a reflection on a case study involving an organization in the United States that navigated the tension between standardization and equity in the redesign of its national university access and persistence curriculum. Leveraging this case study, we present a framework for designing for equity at scale, which includes a series of products to support equity-centered design and a process for equity-centered collaboration.

Overview of the Program and Its Design Challenge

In the United States, there are gross inequities between racial/ethnic groups in regard to graduating from university; six-year university completion rates for four-year institutions show graduation rates for Black and Latine students are 46% and 55% respectively, compared to the graduation rates for white students (67%) and Asian students (72%). GraduationNOW [1] — a U.S.-based organization—developed a university access and persistence program for first-generation, university-going students of color from low-income communities in order to address these inequitable outcomes. University access refers to the processes related to gaining admission into university, and university persistence refers to the processes related to enrolling and successfully completing the requirements for a university degree.

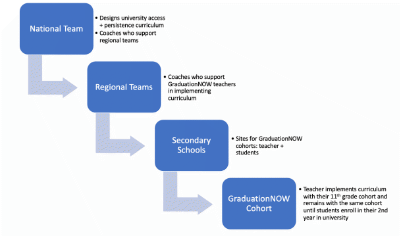

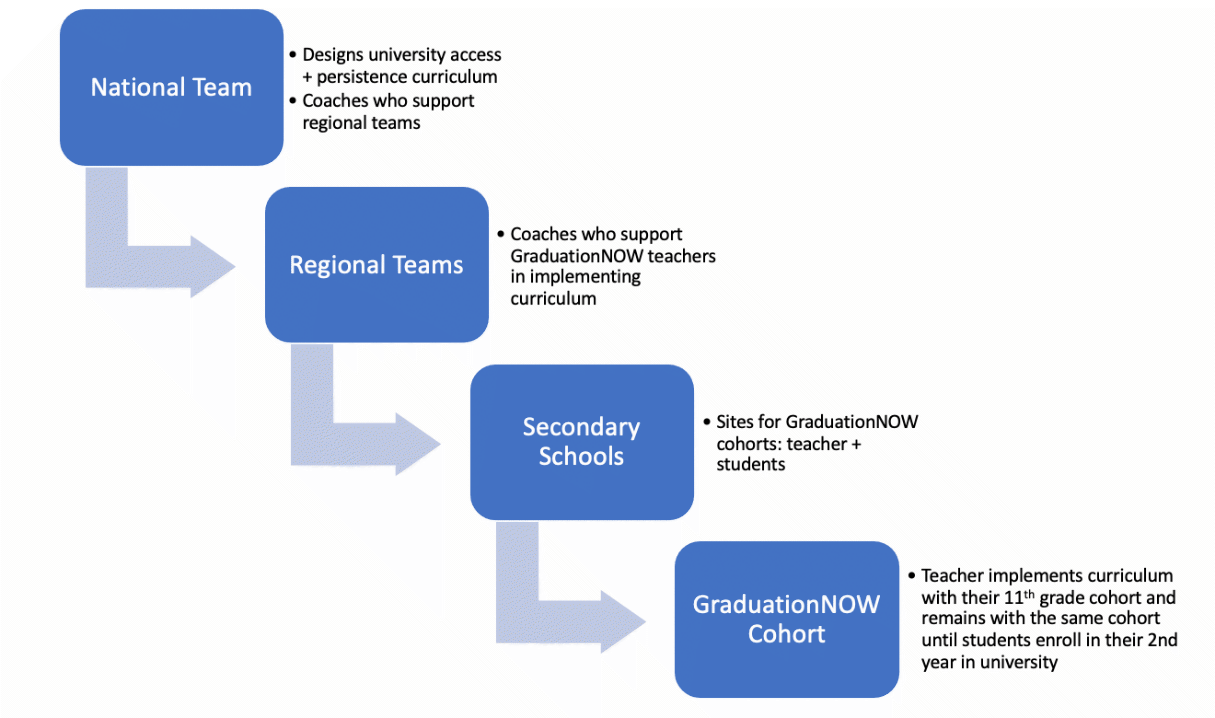

Enlarge…

Core Program Model

GraduationNOW’s program serves students starting in their 11th grade in high school (i.e., second-to-last year), and supports students until they have enrolled for their second year of university for a total of three years of support. Teachers within participating high schools are recruited to teach a GraduationNOW class, and the students enrolled in the class become a cohort that continues the program together with the same teacher as a guide. The core components of the program are: 1) a university access and persistence curriculum; and 2) coaching for teachers who manage cohorts of students. The curriculum was created and developed by a national GraduationNOW team, which then disseminated the curriculum to regional GraduationNOW teams.

The curriculum and the coaching components work in tandem to achieve programmatic aims. The university-access components of the curriculum include test preparation for university admissions exams, support for writing personal statements, encouraging participation in extracurricular activities, and support for completing and submitting applications to university. The university-persistence components consist of supporting students with 1) registering for university classes, 2) signing up for tutoring in university, and 3) ensuring all costs are covered, which includes connecting students with jobs/careers in local industries since most of the students will need part-time to full-time jobs to pay for university costs. The GraduationNOW coaches supported teachers in implementing the curriculum. From a design requirements perspective, it is important to note that some of these elements are required nationwide in order to gain admission to university, and to remain enrolled in good standing (see Figure 2). Within equity-oriented work, it is important to balance helping students recognize inequitable structure / exercise their agency in resisting inequitable structures while also helping them recognize and navigate required elements of the system.

| University Access | University Persistence |

|---|---|

|

|

Diverse Regional Contexts

The program grew from serving one city in the U.S. to serving six cities distributed widely across the nation. The six cities varied across a number of factors such as the size of the immigrant population (e.g., ranging from 14% to 40%), overall population (approximately 500,000 people to approximately 8 million people), and dominant industries that ranged from manufacturing to finance. Racial demographics also varied between the regions. For example, the region with the highest Black population (approximately 50%) was only about 5% Latine, and the region with the largest Latine population (approximately 45%) had a relatively smaller Black population of approximately 23%. These differences in immigration patterns, local industries, and proportions of minoritized populations mean the local histories and current socio-political landscape also varied.

Motivation for the Curriculum Redesign

Prior to the redesign described here, GraduationNOW was relatively successful. Compared to students from similar backgrounds, GraduationNOW students were shown to have higher university going rates (approximately 50% more likely to enroll), higher university persistence rates (approximately 50% more likely to persist), and higher university graduation rates (approximately 40% more likely to graduate). Despite the relative success of the program, staff wanted to further increase the number of students who enrolled in university and persisted through the program. Therefore, the national curriculum team conducted a series of focus groups and one-on-one interviews with former students who left high school or university prior to completing the three-year program to learn more about the factors that pushed them out of school. Analysis of the interview data highlighted some general needs that were beyond the scope of the existing curriculum:

- students struggled to keep up with challenging coursework that would raise their Grade Point Average due to caregiving responsibilities for other family members

- students faced pressure from families to support themselves financially and provide for the household

- students were discouraged from attending better-fit universities to stay close to home; and students felt isolated and alienated on their university campuses

Critically for the current case study, some regional differences emerged as well: undocumented students or students whose parents were undocumented (students or parents who were in the country illegally according to U.S. law) along border states were afraid to complete the government financial aid forms for fear that the government would use their information to find and deport them or their families; and some regional sites had greater access to philanthropic dollars and prestigious universities with outreach programs.

Culturally Relevant Pedagogy & Its Application to the Curriculum Redesign

The curriculum team researched youth development models that could possibly address the challenges that former students mentioned. Through their research, they landed on Culturally Relevant Pedagogy (CRP) as the conceptual framework to redesign the curriculum and shift their coaching practices in order to further increase university-going rates and persistence. Culturally Relevant Pedagogy is a conceptual framework that includes three pillars for the successful teaching and learning of minoritized students: academic achievement, cultural competence, and sociopolitical consciousness (Ladson-Billings, 1995). Academic achievement involves setting high academic expectations for all students and providing support and resources that help students achieve. Cultural competence involves teachers understanding their own culture, and appreciating and understanding the diverse cultural backgrounds of students, and using these knowledges to integrate cultural practices into teaching practices and curriculum. We use the term “knowledges” to emphasize that different cultures have diverse ways of knowing (Tuhiwai Smith, 2012). Lastly, socio-political consciousness involves helping students to understand the social and political structures that impact their lives and to critically examine issues of power and privilege. This includes helping students to recognize and challenge systemic inequities and injustices that may exist within society and within their own communities. Although CRP was initially developed as an in-class pedagogical framework, the tenets of CRP have been applied to the broader landscape of educational landscape using the term Culturally Relevant Education (CRE), which encompasses political ideologies, technical skills, training and development, and readiness within youth-focused organizations (Aronson & Laughter, 2016; Carter-Francique, 2013; Dover, 2013; Gist, 2022). Learning communities that are rooted in CRP take into account student family structures, out-of-school lives, beliefs about school and prior school experiences, and the larger sociopolitical context of the local community (Dover, 2013). The curriculum team felt that emphasis on contextual and familial understanding, and systemic power analysis, could inform the new direction for the curriculum to better address student needs beyond the technical core of university checklist items.

Author Role in the Redesign Process

While the curriculum team was interviewing former students and researching various youth development models, the first author was a program coach for teachers who managed students in their third year of the program—the students’ first year in university —for one of the regional teams in the southern United States. After the decision to shift to a CRP program to better meet the needs of students, the curriculum team launched a search for a team manager to lead the design and implementation of the new CRP curriculum across the six regions. The first author was hired for the new role due to their background as an Urban Education scholar, a teacher who enacted the principles of CRP, and their past contributions to the organizations’ equity and inclusion initiatives. Shortly after beginning their new role, it became evident that the curriculum could not shift without shifting the entire program (i.e., coaching, program evaluation, and school partnerships) to CRP. The tools, processes, and framework that emerged from the curriculum development work that are shared in this paper are a result of the first author’s first-hand experience leading the programmatic changes at GraduationNOW.

Design Dilemma: Standardized Curriculum Design Using CRP

We conceive of the design challenge facing the GraduationNOW national curriculum team as an instance of a general design challenge. On the surface, a standardized curriculum to be used across highly varied contexts is the opposite of culturally relevant education. As in most mid to large-sized countries, each region in the United States has different social, economic, cultural, and political factors that shape students’ lives and affect university access and persistence, and fully implementing culturally relevant education requires context-specific knowledges of local communities and relationships with those communities. At the same time, there were some fundamentals to university access and persistence that were necessary components for all students, and student outcomes would be negatively affected if regional adaptations eliminated or gave too little weight/support to students for any of these necessary components. As a result of these tensions, the overarching design challenge the new curriculum team grappled with was:

How can designers design a standardized, culturally relevant curriculum to be implemented across diverse regions?

We see this design challenge as a particularly intense form of the general need to support local adaptation of curriculum materials (Penuel, Phillips, & Harris, 2014), such as a school district adapting national or regional curriculum components or a group of teachers in a school adapting a school district’s curriculum components for their students. Here cultural relevance is a core element of the materials and local actors are charged with developing the replacement content. In educational design more generally, often only more incidental details are left to local adaptation, or educators are given a small finite list of implementation choices in the designed materials. Finally, we see this design challenge as involving both design principles that shape the structure of what is produced as well as involving design processes for how the designers (both national and local adaptors) do their (re)design work.

A Design Framework for CRP Across Diverse Contexts

The national GraduationNOW curriculum team’s solution to this general design challenge was a design framework that ensured the standardized curriculum was modifiable so that regional teams could adapt the curriculum to their local context. However, this decision to allow and even encourage adaptations made even more salient the other side of the design dilemma: within an adaptable curriculum, how can designers ensure that all students still have the opportunity to access and master the university-focused content that will get them to-and-through university? In collaboration with regional team members, the national curriculum team addressed this concern by developing a framework that articulated what could be adapted within the curriculum to address the local context and student experiences, and explicitly marked what would need to remain constant across contexts (see Figure 3). We see this guideline alongside the other materials presented to regional team members and teachers as a form of educative curriculum materials (Davis & Krajcik, 2005; Davis et al., 2017). In this case, the materials were designed to be educative for regional teams as well.

| What can be adapted? | What cannot be adapted? |

|---|---|

|

|

The new curriculum units were designed to meet university-specific outcomes, which would fall within the “academic achievement” tenet of CRP, and also included features that addressed the two additional tenets of CRP: “cultural competence” and “sociopolitical consciousness”. The rationale for deciding what could not be modified was based on the required deliverables for students to gain admittance to university and persist—writing a personal statement, applying for financial aid, applying for university, enrolling for courses in their first and second year in university, etc., were important for success for students in all city contexts. However, how these deliverables were met could be adapted. For example, in preparation to write their personal statements, engaging students in stories from people who come from similar backgrounds or from their local community could be used instead of the specific resources that were in the national curriculum.

Once the national curriculum team determined what could/should be adapted to local context, and what should remain constant across contexts, they then then considered the capacity implications of having an adaptable curriculum. This had implications for principles for what should be designed and for how it should be designed. In the specific design context, this challenge was phrased as: What tools, processes and structural changes should be made to empower regional staff members and teachers to modify the curriculum to their contexts while staying true to the tenets of Culturally Relevant Education without frequent oversight from national curriculum and coaching team members? The solution to this question was:

- Integrating CRP prompts for teachers within the curriculum modules

- A CRP reflection tool for regions to use as guidelines for coaching and adapting the curriculum to their regional and local context (see Figure 4)

- Re-scoping of regional roles, and the creation of new regional and national roles to meet regional curriculum and coaching needs.

Culturally Relevant Reflection Tool for Local Curriculum Adapters

To further build capacity among regional staff and teachers so that they could modify the curriculum in ways that remained aligned with the tenets of CRE, the national team created a reflection tool based on the pillars of CRP. This tool was used by regional curriculum team members, regional coaches, and teachers to modify the curriculum, design professional development for teachers, and for coaching teachers. Critically, this reflection tool approach allowed the regional team members to be successful without requiring an unsustainable amount of oversight from the national team, an additional equity point we take up in a later section.

There are many reflection questions aligned with the pillars of CRP that could have been included, but the curriculum team did not want to create a tool that would be overwhelming for regional staff and thus less likely to be used. With these goals in mind, the team created 3–4 reflections for each CRP pillar that generally focused on three main themes for staff and teachers: 1) Do I know my cultural values and norms?; 2) Do I know the values and norms of my students and their communities?; and 3) How will I leverage my relationships with my students to leverage their skills to meet our goals?

|

Academic Achievement |

|

|---|---|

|

Cultural Competence |

|

|

Sociopolitical Consciousness |

|

The Resulting Product — The New Culturally Relevant Curriculum

The resulting national curriculum was organized as units, modules within each unit, and daily lessons with prompts within each module (see Figure 5). These materials guided teachers and coaches through the process of producing the deliverables that students would need for university entry or persistence (CRP pillar #1—academic achievement), understand some of the larger systems of race, class, dominant language usage, etc. that affect university access and persistence (CRP Pillar #3—sociopolitical consciousness), and build relationships between teachers and students, and between students and their peers (CRP Pillar #2).

There were also several new resources, tools, and human capital shifts that emerged throughout the design process for creating the curriculum, but the most critical for creating a culturally relevant, inclusive curriculum at scale were the prompts and guides for CRP adaptations within the curriculum materials. To see the ways in which the prompts shaped what local actors did, see Figure 6 for an example of CRP adaptations that a regional team produced. In this example, this portion of the daily lesson focused on preparing students to write their personal statements by showing them short video clips about the power of storytelling. This regional team chose to modify this portion of the lesson to fit their local context by choosing videos of successful people of color who were from the same local area as their students. CRP calls for differentiated plans based on student context, and utilizing narratives of people from the local community to help students reimagine their pathways to

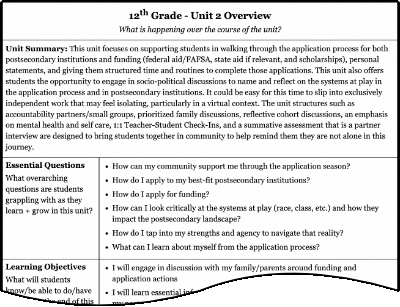

5a – Curriculum unit example

12th Grade - Unit 2 OverviewWhat is happening over the course of the unit? |

|

|---|---|

|

Unit Summary: This unit focuses on supporting students in walking through the application process for both postsecondary institutions and funding (federal aid/FAFSA, state aid if relevant, and scholarships), personal statements, and giving them structured time and routines to complete those applications. This unit also offers students the opportunity to engage in socio-political discussions to name and reflect on the systems at play in the application process and in postsecondary institutions. It could be easy for this time to slip into exclusively independent work that may feel isolating, particularly in a virtual context. The unit structures such as accountability partners/small groups, prioritized family discussions, reflective cohort discussions, an emphasis on mental health and self care, 1:1 Teacher-Student Check-Ins, and a summative assessment that is a partner interview are designed to bring students together in community to help remind them they are not alone in this journey. |

|

Essential QuestionsWhat overarching questions are students grappling with as they learn + grow in this unit? |

|

Learning ObjectivesWhat will students know/be able to do/have in place by the end of this unit? |

|

Learning ObjectivesWhat will students know/be able to do/have in place by the end of this unit? |

12th Grade - Unit 2 Assessment: Final Reflection Project: Peer Interview [INSERT REGIONAL LINK HERE] Students will interview a peer in their cohort about what they have learned and accomplished over the course of this semester and present that interview in a creative way (choice of video, podcast, Powerpoint presentation, or an interview transcript with visuals). The prompts ask students to consider their own strengths, their knowledge of systems, mental health, and the role of their community. Students will also reflect on the similarities and differences they noticed between the person they interviewed and their own experiences. |

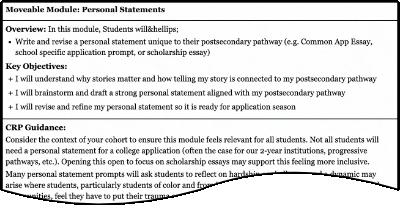

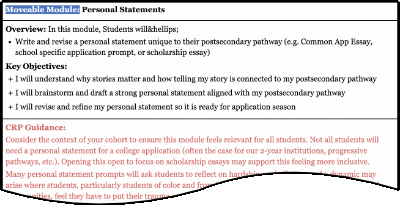

5b – Module example

Moveable Module: Personal Statements |

|

Overview: In this module, Students will…

Key Objectives:

|

|

CRP Guidance: Consider the context of your cohort to ensure this module feels relevant for all students. Not all students will need a personal statement for a college application (often the case for our 2-year institutions, progressive pathways, etc.). Opening this open to focus on scholarship essays may support this feeling more inclusive. Many personal statement prompts will ask students to reflect on hardship or challenges and a dynamic may arise where students, particularly students of color and from low-income backgrounds or other marginalized communities, feel they have to put their trauma out there to admissions committees (both because of the prompt and because of the systems at play in admissions committees). As you facilitate this module, how can you support them in telling stories that are empowering and telling the stories they want to tell rather than what they think they have to share? |

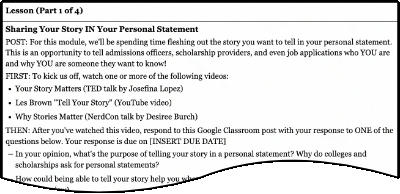

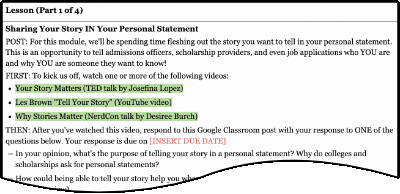

5c – Lesson example

Lesson (Part 1 of 4) |

Sharing Your Story IN Your Personal StatementPOST: For this module, we'll be spending time fleshing out the story you want to tell in your personal statement. This is an opportunity to tell admissions officers, scholarship providers, and even job applications who YOU are and why YOU are someone they want to know! FIRST: To kick us off, watch one or more of the following videos:

THEN: After you've watched this video, respond to this Google Classroom post with your response to ONE of the questions below. Your response is due on [INSERT DUE DATE]

|

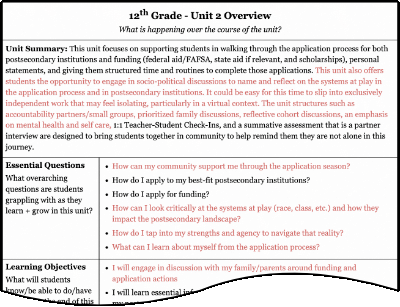

6a – Example regional modifications to a curriculum unit

| Text in red font are examples of prompts aligned to cultural competence or socio-political consciousness. Areas highlighted in blue are examples of suggested areas for regions to adapt to their context. | |

12th Grade - Unit 2 OverviewWhat is happening over the course of the unit? |

|

|---|---|

|

Unit Summary: This unit focuses on supporting students in walking through the application process for both postsecondary institutions and funding (federal aid/FAFSA, state aid if relevant, and scholarships), personal statements, and giving them structured time and routines to complete those applications. This unit also offers students the opportunity to engage in socio-political discussions to name and reflect on the systems at play in the application process and in postsecondary institutions. It could be easy for this time to slip into exclusively independent work that may feel isolating, particularly in a virtual context. The unit structures such as accountability partners/small groups, prioritized family discussions, reflective cohort discussions, an emphasis on mental health and self care, 1:1 Teacher-Student Check-Ins, and a summative assessment that is a partner interview are designed to bring students together in community to help remind them they are not alone in this journey. |

|

Essential QuestionsWhat overarching questions are students grappling with as they learn + grow in this unit? |

|

Learning ObjectivesWhat will students know/be able to do/have in place by the end of this unit? |

|

Learning ObjectivesWhat will students know/be able to do/have in place by the end of this unit? |

12th Grade - Unit 2 Assessment: Final Reflection Project: Peer Interview [INSERT REGIONAL LINK HERE] Students will interview a peer in their cohort about what they have learned and accomplished over the course of this semester and present that interview in a creative way (choice of video, podcast, Powerpoint presentation, or an interview transcript with visuals). The prompts ask students to consider their own strengths, their knowledge of systems, mental health, and the role of their community. Students will also reflect on the similarities and differences they noticed between the person they interviewed and their own experiences. |

6b – Example regional modifications to a module

| Text in red font are examples of prompts aligned to cultural competence or socio-political consciousness. Areas highlighted in blue are examples of suggested areas for regions to adapt to their context. | |

Moveable Module: Personal Statements |

|

|

Overview: In this module, Students will…

Key Objectives:

|

|

|

CRP Guidance: Consider the context of your cohort to ensure this module feels relevant for all students. Not all students will need a personal statement for a college application (often the case for our 2-year institutions, progressive pathways, etc.). Opening this open to focus on scholarship essays may support this feeling more inclusive. Many personal statement prompts will ask students to reflect on hardship or challenges and a dynamic may arise where students, particularly students of color and from low-income backgrounds or other marginalized communities, feel they have to put their trauma out there to admissions committees (both because of the prompt and because of the systems at play in admissions committees). As you facilitate this module, how can you support them in telling stories that are empowering and telling the stories they want to tell rather than what they think they have to share? |

|

6c – Example regional modifications to a lesson

| Text in red font are examples of prompts aligned to cultural competence or socio-political consciousness. The area highlighted in green is an example of one regional adaptation to a daily lesson. | |

Lesson (Part 1 of 4) |

|

Sharing Your Story IN Your Personal StatementPOST: For this module, we'll be spending time fleshing out the story you want to tell in your personal statement. This is an opportunity to tell admissions officers, scholarship providers, and even job applications who YOU are and why YOU are someone they want to know! FIRST: To kick us off, watch one or more of the following videos:

THEN: After you've watched this video, respond to this Google Classroom post with your response to ONE of the questions below. Your response is due on [INSERT DUE DATE]

|

|

Example of how a region adapted this portion of a lessonRegional Context: One of GraduationNOW's southeastern regional sites was located in a large metropolitan area and served a population of majority Black students. This metropolitan region has a large proportion of Black people who completed postsecondary education and were born and raised in the same community as the GraduationNOW students. Regional Adaptation: This region removed 2 video clips and instead showed short inspirational storytelling videos from successful people who were from the same communities as students. |

|

New and Redesigned Roles to Meet Capacity Needs

Another part of the redesign to support regional staff members in making CRP-shifts in the curriculum was to re-scope regional roles to now prioritize CRP knowledges and implementation experience, and the creation of new regional and national roles such as a regional director of curriculum and coaching who would be responsible for implementing the curriculum in each region and supporting with CRP adaptations. The national team created a role to support the new regional curriculum and coaching role. These new and redesigned roles helped to increase capacity for training and making regional adaptations to the curriculum. Such additional / changes roles are not typically included within the educative curriculum materials approach to supporting productive adaptation.

Foundational Principles for Equity-Centered Collaboration & Design Processes

The prior section focused on what was designed. Here we turn to how it was designed. We argue that cultivating equity in the design process itself is important to producing an equity-centered product. Prior to the formal shift in curriculum and throughout the curriculum overhaul process, GraduationNOW was undergoing a series of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives to increase retention of staff of color and create a more equitable, inclusive environment for staff in general. One of the motivations for DEI work was due to hierarchical decision-making that did not include the input of those who would be most affected by those decisions. This asymmetrical decision-making power structure left many staff members feeling disempowered and wary of new programmatic initiatives, especially staff of color. Further, in the past, the approach to regional modifications to the curriculum was an analogous hierarchical process where the national team—including the curriculum team—was charged with forcing regions to comply with the standardized curriculum rather than allowing regional adaptation. With the shift to CRP, it did not make sense to create a culturally relevant curriculum and coaching model while perpetuating exclusive, dominant decision-making practices. Therefore, the national curriculum team asked the question, what would an inclusive, culturally relevant design process look like? What principles would undergird a process aligned to these values?

In order to enact an equitable, inclusive process, the national team changed the design process to redistribute power between people with marginalized and privileged social identities in the form of resources, authority, and decision-making. Those with marginalized identities, those who would be directly impacted by the change of the curriculum and its implementation, and those who demonstrated equity and inclusion in action, were given decision-making power in this process. The following principles (Figure 7) and their aligned reflection questions emerged from the collaborative design process and provided the foundation for equity-centered collaboration and design experiences.

The accompanying reflection questions for Make Power Explicit and Sustainability emerged organically while planning the design process because the individuals leading the initiative embodied the values (Principle #2) of culturally relevant mindsets and practices. The reflection questions that provided the foundation for the CRP program shifts were eventually synthesized into these three principles later in the design process, yet no formal checkpoints were implemented because the team organically assessed equity whenever decisions were made that impacted the product or the process. Figure 7 also highlights examples of each principle in practice which includes a representative, collaborative design structure, allocation of resources to program areas of need, and advocacy to shift design team roles to prevent heavy workloads.

|

Principle |

Reflection Questions Before and During Design Process |

Example of each Principle in Action |

|---|---|---|

|

#1: Make Power Explicit |

|

|

|

#2: Embodiment of Values |

|

|

|

#3: Sustainability |

|

|

Stakeholder Reflections on the Design Process

There were a number of positive outcomes that emerged from the CRP design process among staff. When the entire staff of approximately 150 people were surveyed about the direction of the new curriculum, 100% of respondents said they agreed or strongly agreed with the shifts in the curriculum. One design team member who was not on the curriculum team said, “This is the most egalitarian team I have ever been a part of.” [2] The positive experiences of design team members and the overwhelming support of the full staff speaks to the importance of forming a design team that embodies equity-centered practice.

However, some challenges emerged with senior leadership. While senior leadership felt the CRP curriculum was moving in the right direction, some senior leaders on the national team expressed dissatisfaction with having no decision-making power in the design process or product. The design team collectively decided to continue centering the most marginalized voices in the organization—which did not include senior leadership—and instead chose for them to engage in a workshop that illuminated the need for more collaborative structures that decentered their power and that aligned to their verbal DEI commitments. We believe it is important to briefly name the challenges that did arise with some senior leaders because research highlights the critical role of senior leadership in advancing or stymying equity-centered initiatives (Pillai, 2021). It is important to maintain transparent communication with senior leaders and engage them in thoughtful, asset-based learning experiences, but decision-making power should remain with 1) those who have a demonstrated history of positive, culturally responsive relationships and thought-leadership centering equity and inclusion, and 2) those who are most proximate to the work to enact equity principles.

General Process for Equity-Centered Design at Scale

This section outlines a general step-by-step process for adapting the processes and tools presented in this paper to design within other content areas and organizational contexts. The specific tools used in the GraduationNOW context have been modified to generalize or remove language that is specific to GraduationNOW. This set of processes and tools does not represent the only possible path toward equity-centered design; we encourage designers to modify and adapt as needed. Like the design process GraduationNOW undertook, these recommended steps assume there are a larger set of fixed criteria or content that are required for the program/school/organizational context (e.g., standards for each academic subject area, learning objectives across sites, etc.).

Step One: Identify team members to lead design efforts

- Use principles #1 and #2 to determine the core team who will spearhead the design process

- GraduationNOW example: the national curriculum team spearheaded this process

- The core team will then lead the recruitment and selection for a larger design team using principles #1 and #2 as a guide

- GraduationNOW example: recruitment of regional liaisons and former students

- Negotiate team roles and determine what capacity looks like (principle #3)

- GraduationNOW example: design team members had some responsibilities shifted to allow space to design the new content, and new regional and national team roles were created

|

Principle |

Example Reflection Questions Before and During Design Process |

|---|---|

|

Principle #1: Make Power Explicit |

|

|

Principle #2: Embodiment of Equity-Centered Values |

|

|

Principle #3: Sustainability |

|

Step Two: Determine core components of content that remain constant across contexts, and determine what elements are adaptable

- What are the core components of your program/content that must be standardized across contexts?

- GraduationNOW example: SAT/ACT testing (standardized test), personal statement essay, financial aid application, etc.

- Reflect on why these are considered core components; are they required by an administrative entity? Are they tied to fixed learning objectives? What is the rationale for identifying these as standardized requirements?

- GraduationNOW example: requirements for university applications and requirements to remain in good standing within universities

- Determine what elements are adaptable

- GraduationNOW example: lessons priming for family histories and storytelling are adaptable to local context

|

What Do We Adapt? |

What Remains Constant? |

|---|---|

|

|

Step Three: Develop guidelines for adaptations

- If people outside of the design team are modifying artifacts, what criteria are they using to ensure core content knowledges and skill are still embedded within materials, and cultural and sociopolitical consciousness?

- GraduationNOW example: CRP reflection tool

|

Academic Achievement |

|

|---|---|

|

Cultural Competence |

|

|

Sociopolitical Consciousness |

|

Step Four: Design products

- Create new curricular materials

- GraduationNOW example: units, modules, and daily lessons

- Determine training and development needs to implement with fidelity

We recommend engaging senior leaders and those who will be impacted by the design changes on a consistent basis to keep them informed of the changes and to solicit feedback, when feedback aligns with the foundational equity principles presented in Figure 8. When engaging with different stakeholders we suggest leveraging the three core tenets of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy to guide interactions. These reflection questions in Figure 10 can be used to have equity-centered conversations, design programming/content, coach and train stakeholders, and plan content.

Conclusion

This paper presents a framework and reflection tools for equity-centered design at scale that emerged from a program shift toward culturally relevant education. This framework includes an adaptation guide for each site to use in adapting the curriculum to their local context, a coaching and design tool that regions could use when adapting the curriculum to ensure the adaptations align with CRP, and the principles that guided both process and product.

Implications for Design at Scale

At the largest grain size, the framework, adaptation guides, and overall design/ collaboration process approach could be considered a worked example that could be then adapted for use in other educational materials design contexts, whether of curriculum materials, assessments, or professional learning events. At the more fine-grained level, many of the specific details (especially the reflection questions) are likely to be useful for other efforts to create culturally relevant materials for use across culturally diverse sites.

However, we do note that the collaborative, equitable process described in this paper was made possible by an overwhelming majority of staff who already embodied many of the mindsets and actions that a CRP program requires. This was due to having a racially diverse, people-first Human Resources team who recruited and hired talent based on both skill and equity-mindset. Without a caring, deeply-committed staff, initiating and implementing a CRP program would likely be more challenging.

References

Aronson, B., & Laughter, J. (2016). The theory and practice of culturally relevant education: A synthesis of research across content areas. Review of Educational Research, 86(1), 163-206.

Bautista, A., Bull, R., Ng, E. L., & Lee, K. (2021). “That’s just impossible in my kindergarten.” Advocating for ‘glocal' early childhood curriculum frameworks. Policy Futures in Education, 19(2), 155-174.

Carter-Francique, A. R. (2013). Black female collegiate athlete experiences in a culturally relevant leadership program. The National Journal of Urban Education & Practice, 7(2), 87-106.

Dover, A. G. (2013). Teaching for social justice: From conceptual frameworks to classroom practices. Multicultural perspectives, 15(1), 3-11.

Gist, C. D. (2022). Shifting dominant narratives of teacher development: New directions for expanding access to the educator workforce through grow your own programs. Educational Researcher, 51(1), 51-57.

Davis, E. A., & Krajcik, J. S. (2005). Designing educative curriculum materials to promote teacher learning. Educational Researcher, 34(3), 3-14.

Davis, E. A., Palincsar, A. S., Smith, P. S., Arias, A. M., & Kademian, S. M. (2017). Educative curriculum materials: Uptake, impact, and implications for research and design. Educational Researcher, 46(6), 293-304.

Jones, R., Holton, W., & Joseph, M. (2019). Call me mister: Black male grow your own program. Teacher Education Quarterly, 46(1), 55-68.

Jurado de Los Santos, P., Moreno-Guerrero, A. J., Marín-Marín, J. A., & Soler Costa, R. (2020). The term equity in education: A literature review with scientific mapping in Web of Science. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3526.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491.

Penuel, W. R., Phillips, R. S., & Harris, C. J. (2014). Analysing teachers’ curriculum implementation from integrity and actor-oriented perspectives. Journal of Curriculum studies, 46(6), 751-777.

Pillai, R. (2021). Cultural dynamics in the workplace™: 5 key factors in driving successful DEI initiatives to achieve business outcomes. Center for Diversity & Inclusion.

Tuhiwai Smith, L. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples. Zed Books.

Yang, W., & Li, H. (2022). Curriculum hybridization and cultural glocalization: A scoping review of international research on early childhood curriculum in China and Singapore. ECNU Review of Education, 20965311221092036.