30 Design Strategies and Tactics from 40 Years of Investigation

Appendix: Further information and examples

Use engineering methods

Turning prior research and creative ideas for improvement into robust tools and processes that work well in practice requires research in the engineering tradition (Burkhardt 2006). The process is complicated and expensive but worthwhile – there is a huge difference in students' learning experiences between the best and the standard "perfectly good" materials. The process involves:

- a specific improvement goal, grounded in robust aspects of theory from prior research. Research insights are both a key input and a second kind of output from the design and development process.

- design tactics that combine these core ideas with the design team's creativity, always providing close support with the pedagogical challenges

- flexibility in the draft materials that affords adaptation to the range of contexts across the intended user community

- rapid prototyping followed by iterative refinement cycles in increasingly realistic circumstances, with

- feedback from each round of trials that is rich and detailed enough to ensure the robustness and adaptability of the final reproducible materials, with

- continued refinement on the basis of post-implementation feedback 'from the field' – this also informs thinking for future developments.

MAP Website

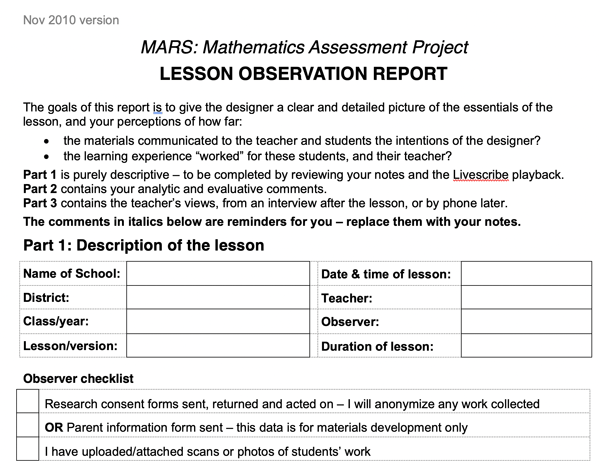

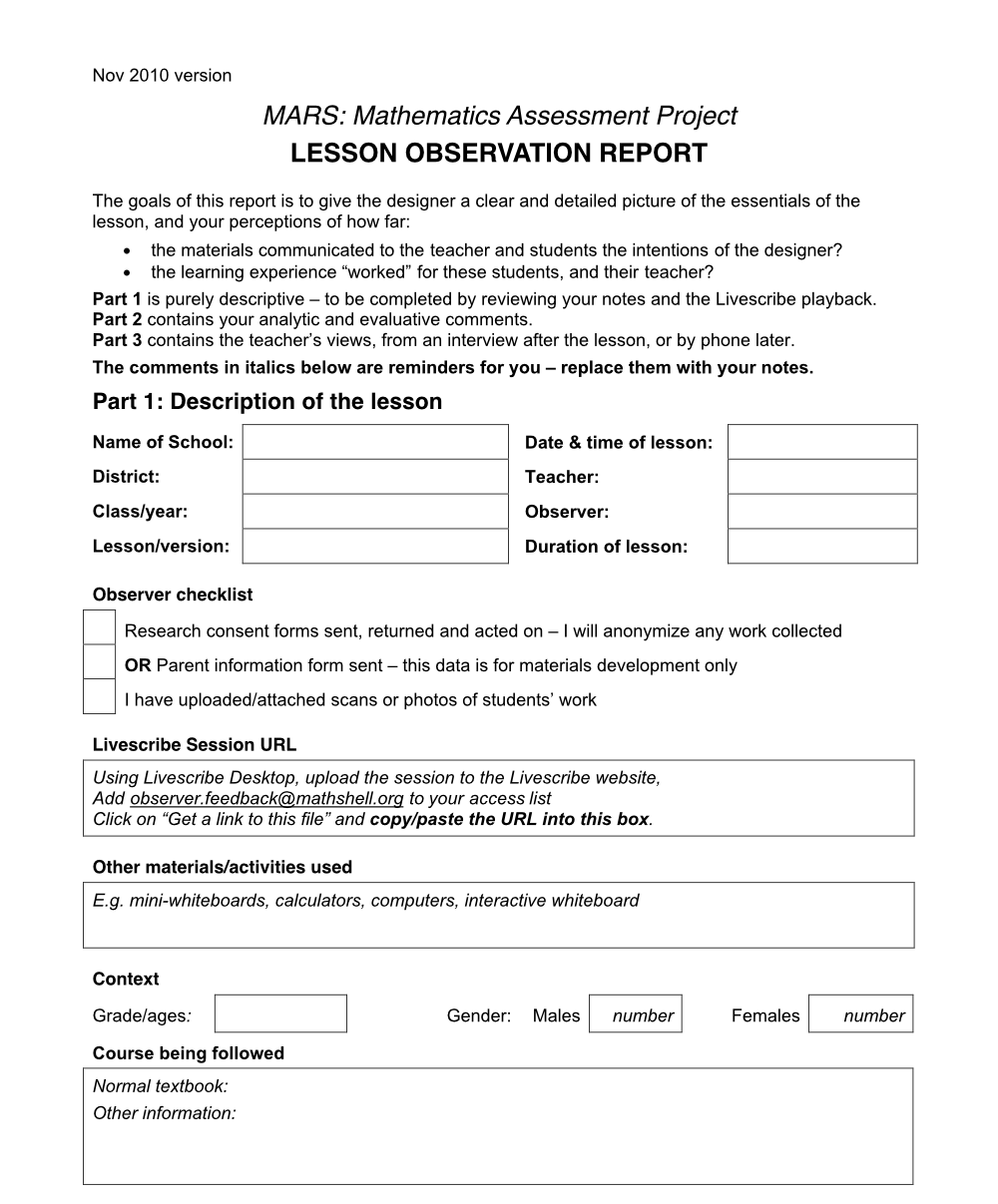

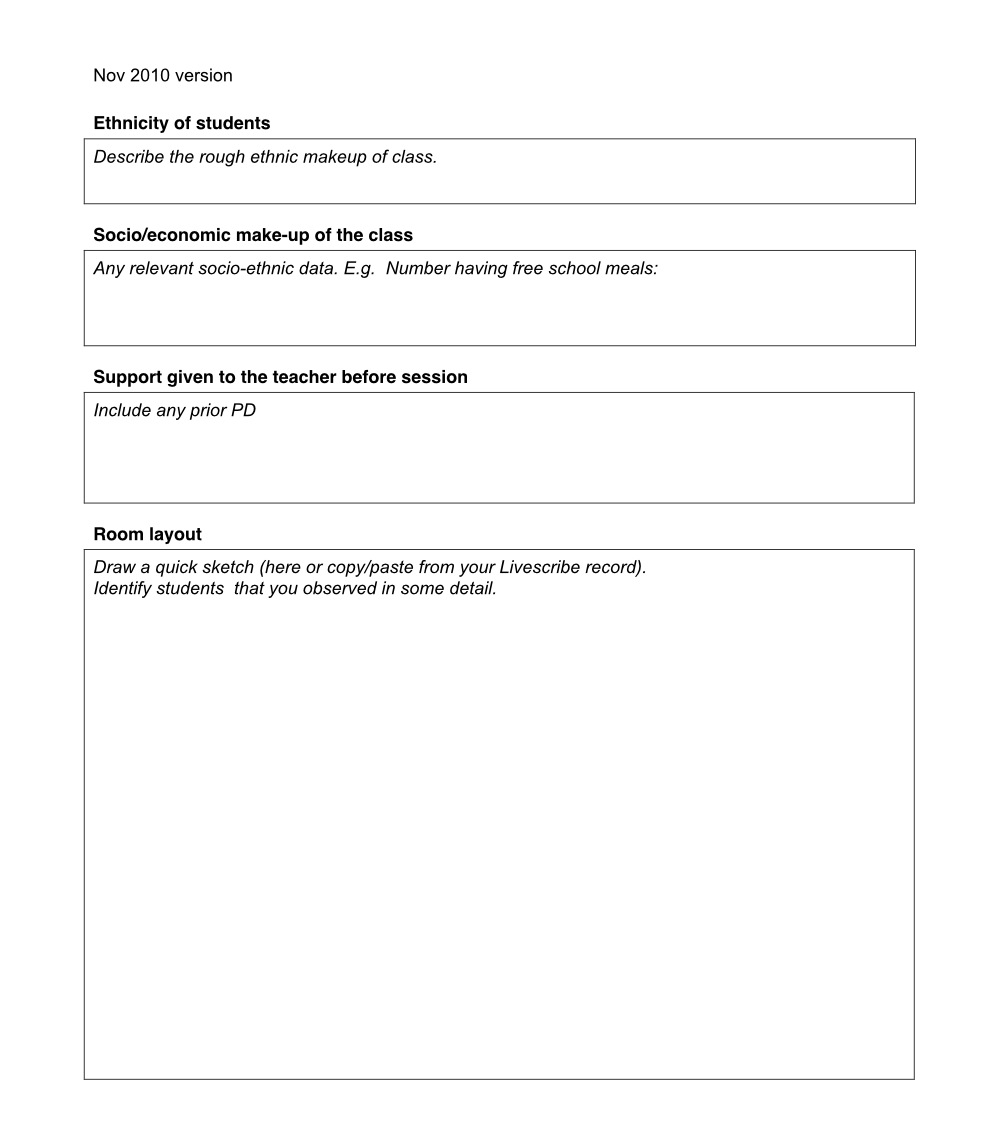

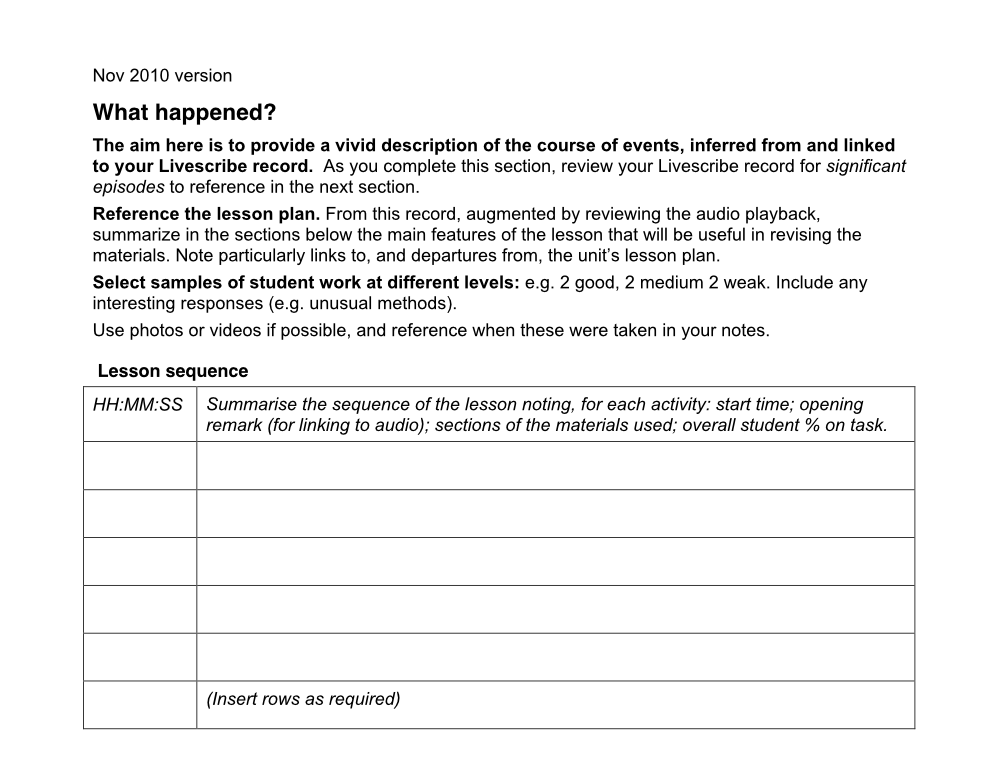

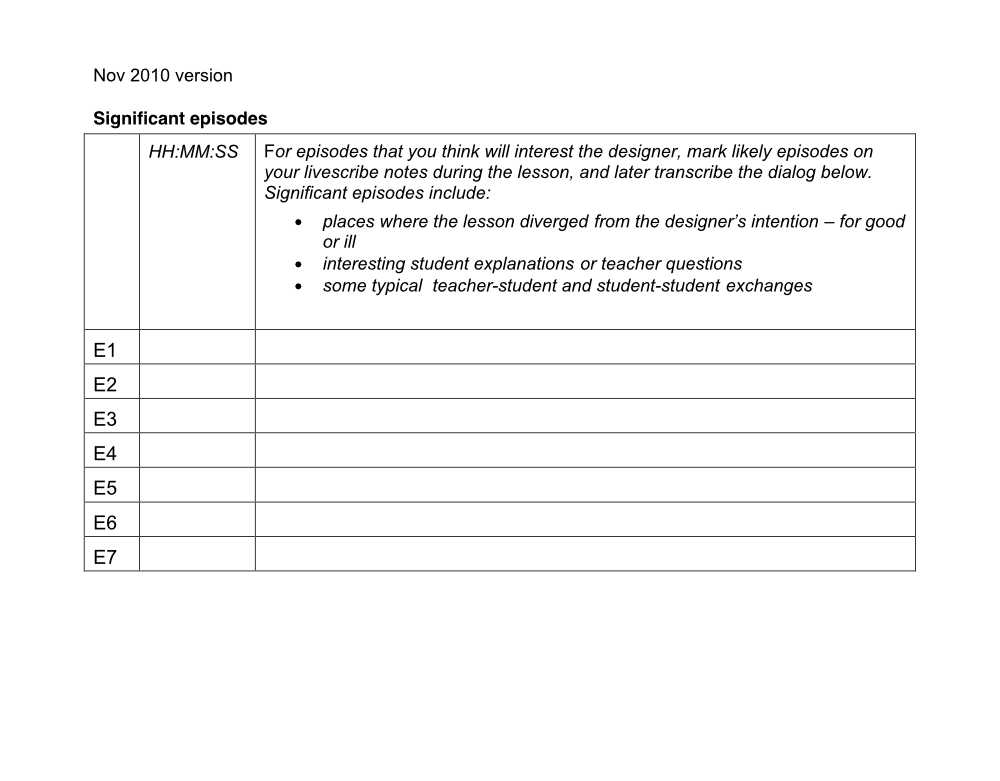

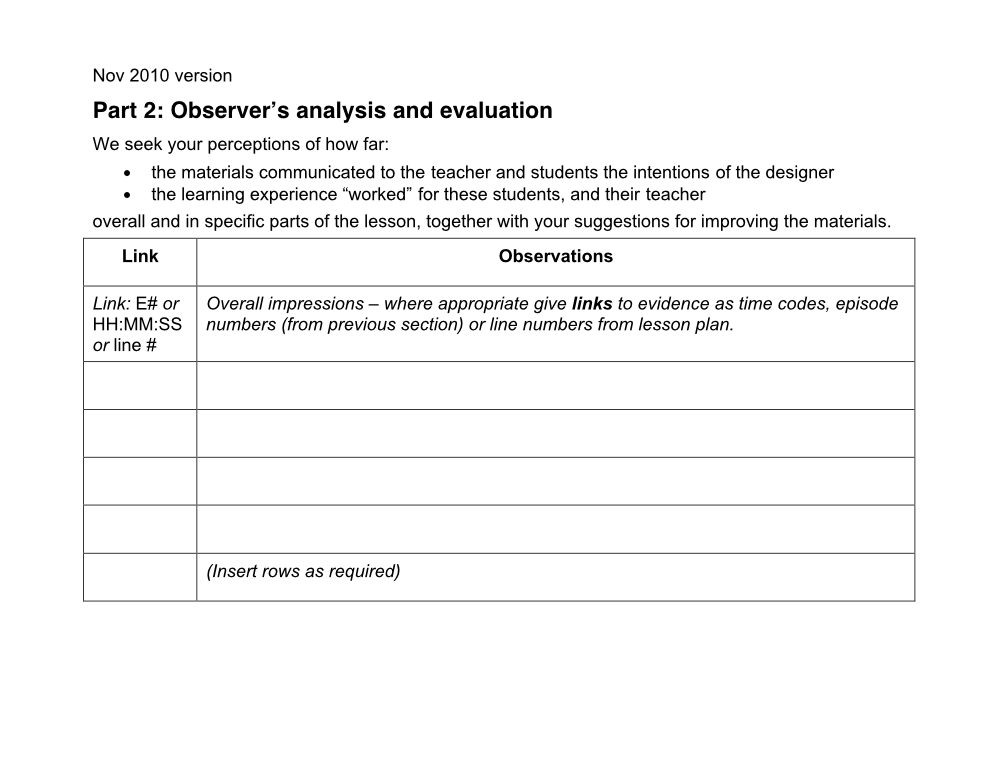

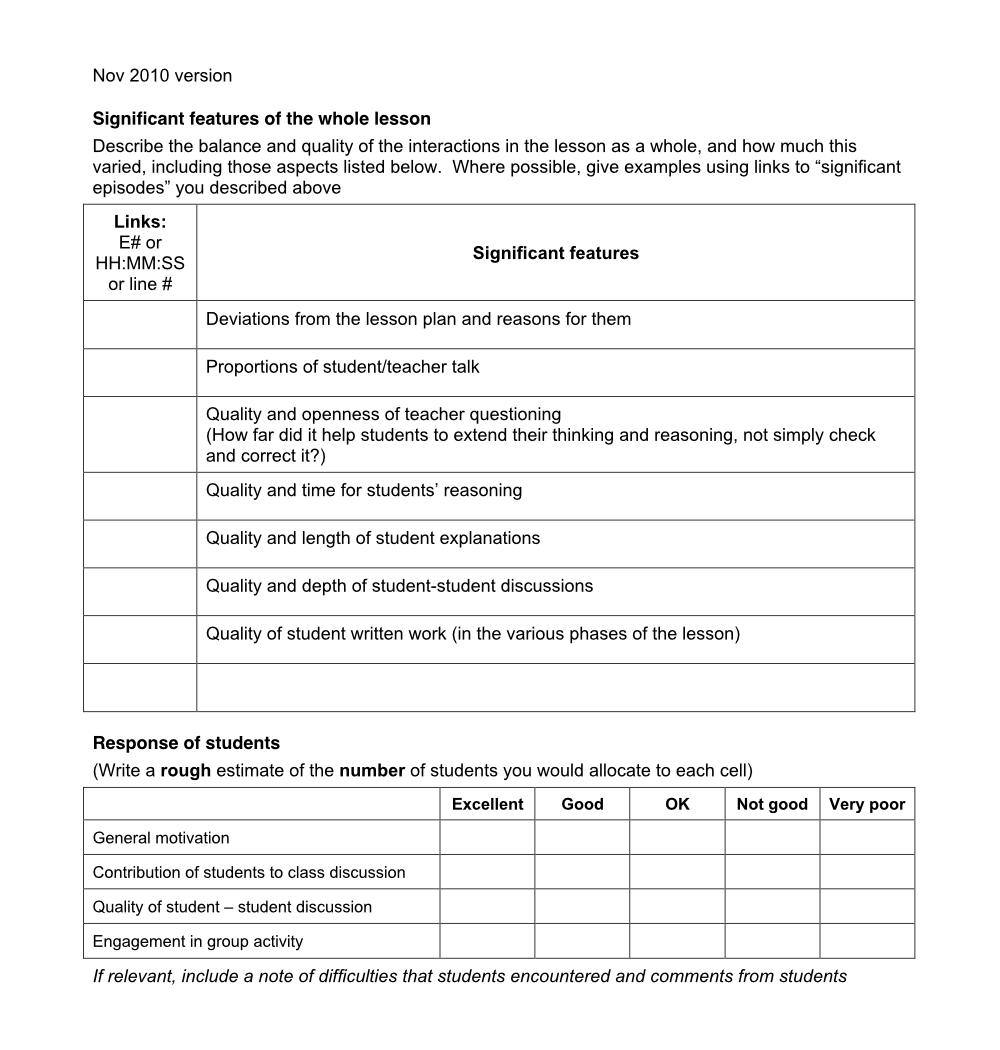

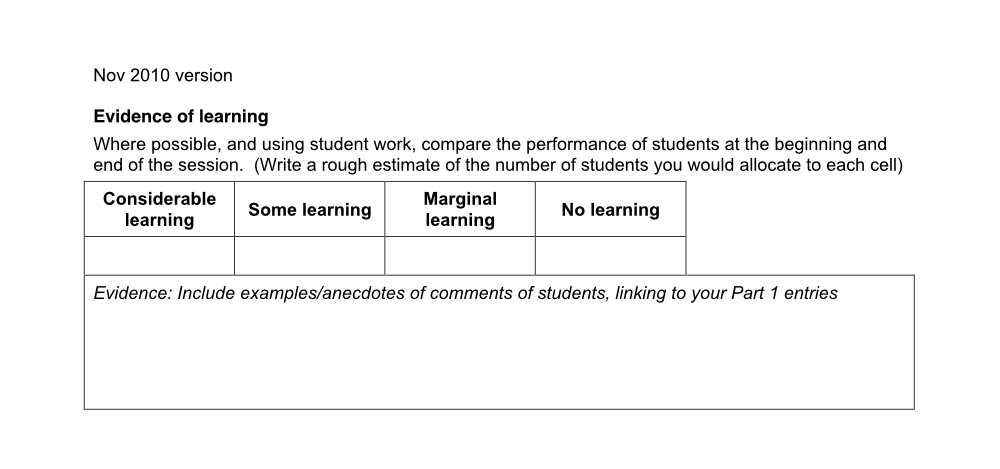

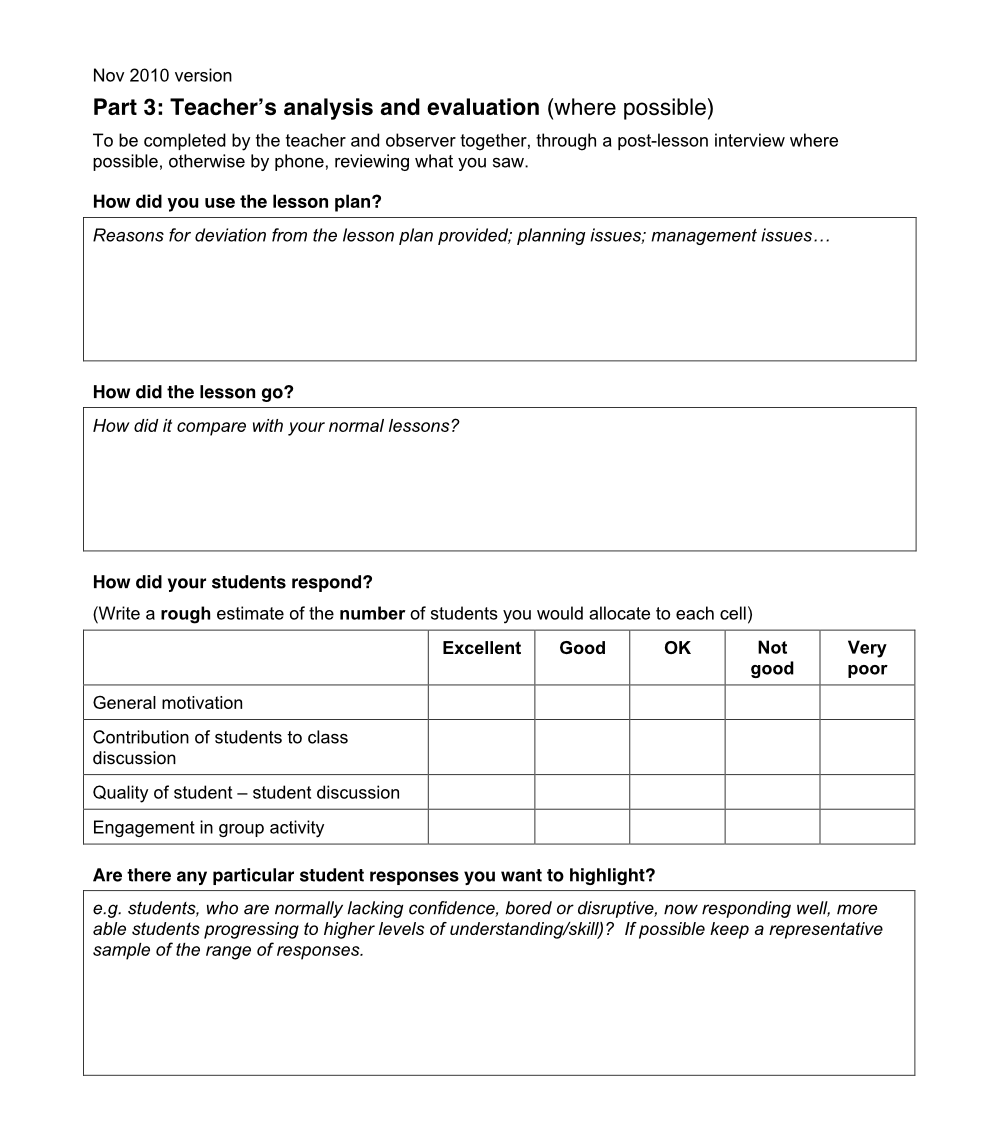

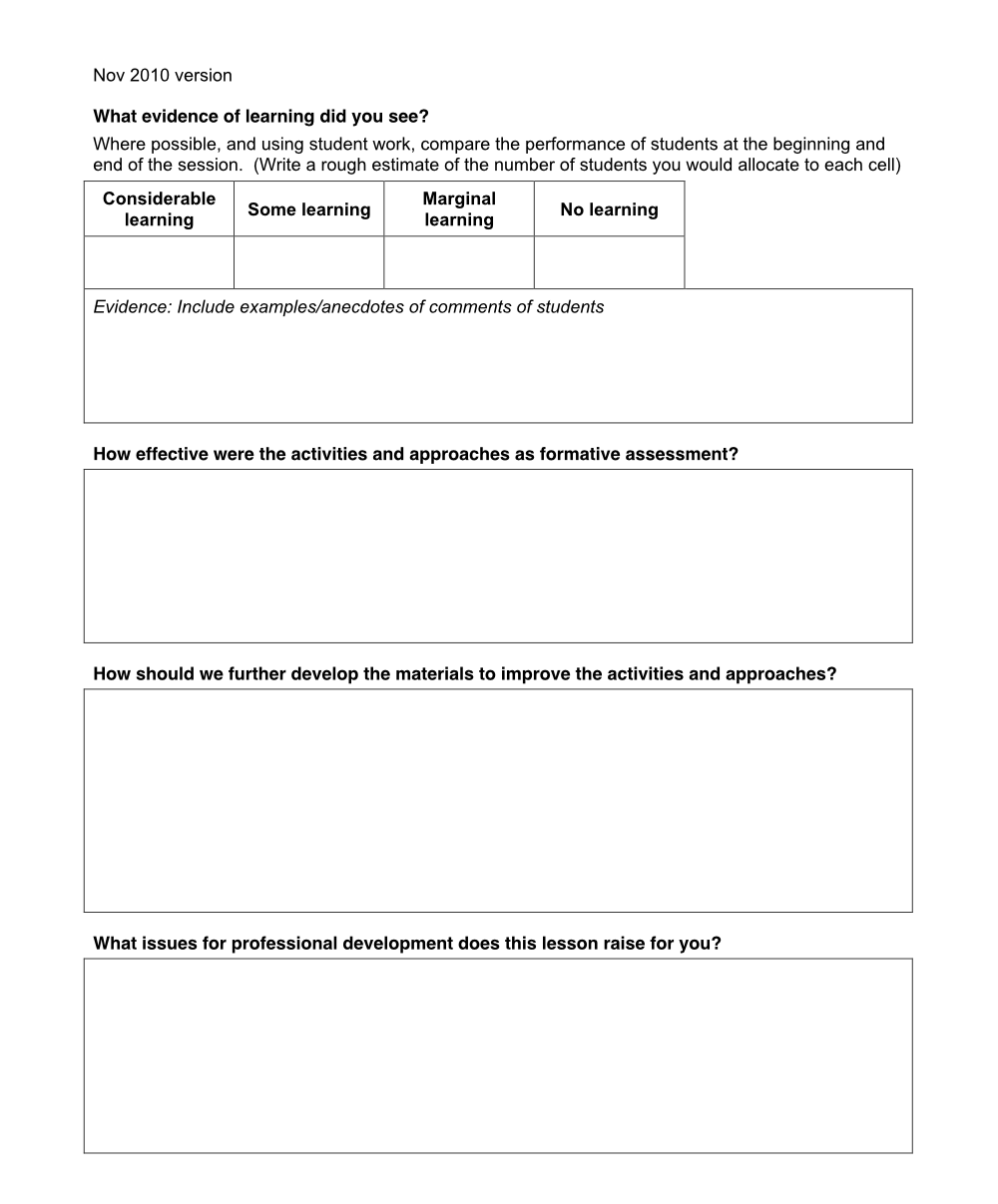

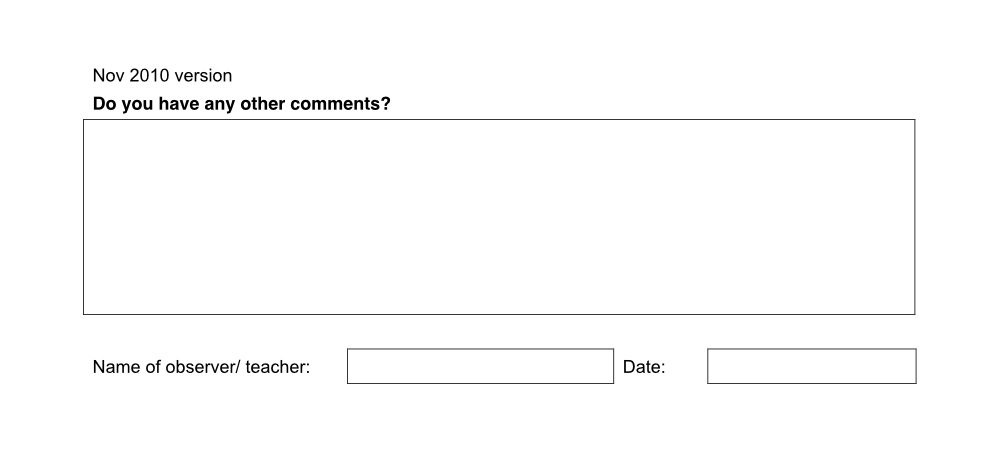

The process is exemplified by the lesson development in the Mathematics Assessment Project. The goal was to see how far typical mathematics teachers in supportive school environments (a specific user group, 3 and 4 above) could be enabled to implement high-quality formative assessment for learning (a specific improvement goal guided by research, see Black and Wiliam 1998) in their own classrooms, when primarily guided by published lesson materials designed for this purpose. The design team had a track record of outstanding design achievements (point 2 above). Flexibility (3) was addressed through advice on ways to time these supplementary lessons so as to best enhance whatever mathematics curriculum the school is using. Feedback of sufficient quality for guiding revisions (5 and 4) was based on direct observation of a handful of lessons at each stage by experienced classroom observers using a structured protocol. This provided feedback of sufficient quality to guide an evidence-based revision process.

Enlarge…

Link to document

This emphasises what actually happened in the lesson and its relation to the design intentions. The report also included interviews with the teachers. The 700 lesson reports together provided research insights to guide future work (1); in this it was supplemented by independent evaluations and informal feedback from users (6). The work is described in (Burkhardt and Swan 2014) and analysed as formative assessment in (Burkhardt and Schoenfeld 2019), which reviews the evaluative evidence showing the power of the lessons as teacher professional development as well in student learning – and example of the payoff from high-quality design and development.

Rigorous qualitative research methods are involved, not just for the input phase but throughout the process: in the selection and the training of designers; the choice of sample classrooms, or other contexts, for trials at each stage of development; the design of protocols for capturing the relevant information in the most cost-effective way, for example for classroom observation; the form of presentation of the materials to optimise communication, which always involves choices that balance information with usability – a typical design trade-off.

A lesson revision process

This account, while broadly applicable, is based on the working of the MAP design team. Formative assessment lessons involve relatively complex teacher-student and student-student interactions that are unfamiliar to many teachers. Feedback on what happens in lessons needs to be informed by rich and detailed information about those complex processes, if it is to inform legitimate revisions. The model for producing a revised lesson plan from a trial version of a lesson plan consists of three phases: analysis; a review meeting; revising the lesson

Analysis phase: One member of the design team takes the role of analyst for each trial lesson. He or she is not the original designer of the lesson – this separation of roles enhances objective analysis of trial evidence, and increases the range of the team’s understandings and expertise being applied to the design of each lesson. The designer is nevertheless intrinsic to the revision process.

Once trial data are available, the analyst works systematically through each lesson observation report, the transcription evidence, and student work, noting teacher, student and observer responses. He or she synthesizes the evidence arising in different parts of the lesson observation report on particular issues, and identifies themes emerging across different observer reports, looking for both grounds for revision of the lesson plan and evidence of what already works well.

The analyst compiles an evidence-based report, highlighting issues that have arisen and making recommendations for revision. The recommendations in the report may be particular to the lesson being analyzed, or general, if similar issues emerge in other lessons. The analyst’s report is circulated to the team and a meeting is arranged.

The review meeting: At each review meeting members of the design team use the analytical report to frame discussion of the lesson. The meeting, chaired by the lead designer, includes the lesson's designer and the analyst; a second analyst often also attends. This helps us to identify themes emerging across series of lesson observation reports, to notice issues pertinent to particular types of lessons, and to work on house styles.

All participants in the meeting are familiar with the analyst’s report, lesson plan, observation reports and student work, and with the broader context of series of lessons. The team clarifies issues emerging from the lesson observation evidence, and recommends design decisions based on the evidence. The analyst’s report frames the discussion but does not determine the outcomes. The decisions on what to revise, and how, are thus team decisions triangulating at least three expert perspectives informed by evidence on the lesson, triangulating different sources of information, using one part of a lesson observation report to interrogate another. Issues that emerge across series of lessons also need to be taken into account.

The design decisions are framed by our theoretical understandings of mathematics, of school mathematics, of classrooms and teaching and of relevant research evidence. The trial evidence alone thus does not determine which revision decisions to make but does shape and inform our expert decisions about how to revise.

Lesson revision phase: Once revision decisions have been made by the team, the analyst revises the lesson. The revised version is circulated to colleagues for agreement and when accepted, there is a signing off meeting. The lesson plan is then formatted and made available in electronic form, ready for subsequent trials.

References

Burkhardt, H, & Schoenfeld, A. H. (2019). Formative Assessment in Mathematics. In R. Bennett, G. Cizek, & H. Andrade (Eds), Handbook of Formative Assessment in the Disciplines. New York: Routledge.

Burkhardt, H. and Swan, M. (2014) Lesson design for formative assessment, Educational Designer, 2(7). Retrieved from: http://www.educationaldesigner.org/ed/volume2/issue7/article24